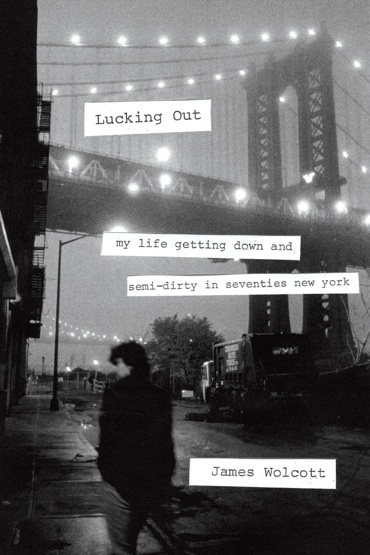

As a kind of followup to the Kael bio, I also read the James Wolcott memoir, Lucking Out: My Life Getting Down and Semi-Dirty in Seventies New York. I somehow did not realize that Wolcott (whom I associate with Vanity Fair) began his career and was generally known for years not only as a Village Voice writer but as a sometime rock critic. (“Somehow” because I was a devoted reader of the Voice, especially its music section, in the early & mid 1980s, not long after his time writing for it.) Walcott dropped out of Frostberg State U. in Maryland as a sophomore after he sent a piece of his to Norman Mailer, who promised to put a word in for him to a Voice editor once Wolcott graduated. Wolcott proceeded to quit school on the spot and move to NYC and eventually, through persistence/ refusing to go away, parlayed that recommendation into a job answering phones, from where he began to do some writing. Pretty soon, at age 19-20, he was covering the nascent punk rock scene — he published one of the first raves about Patti Smith, well before the release of Horses — and covered television as a regular beat (not to mention the band Television, along with Talking Heads and other CBGBs bands). He soon became a protege/buddy of Pauline Kael’s (he became somewhat notorious for a later Vanity Fair take-down of her followers “the Paulettes,” which was taken as apostasy and an act of betrayal –one of her other rival proteges labels him a “self-promoting asshole” or some such in her biography; he does not discuss this in the book but it came up in the Fresh Air interview); became obsessed with the New York City Ballet; and he also dedicates a section of the book to Times Square pornography in the 1970s. He doesn’t push this too strongly but there’s an implicit thread in the book in which Wolcott charts his own experience as a fan, critic, and consumer of these different parallel art forms and media (punk rock, movies, ballet, porn), within all of which in this period the representation and expression of bodies, sexuality, physicality, gender transformed. Wolcott is very much a critic and an observer; he refers in passing to his own sex life, for example, but greater emphasis is placed on the represented bodies and lives he wrote about. As “semi-dirty” in the title hints, Wolcott portrays himself as a watcher, a bit prudish and reserved even in the grimiest occasions in Times Square or the Bowery or otherwhere in a NYC that was close to falling apart entirely:

It wasn’t just the criminality that kept you laser-alert, the muggings and subway-car shakedowns, it was the crazy paroxyms that punctuated the city, the sense that much of the social contract had suffered a psychotic break. That strip of upper Broadway [where Wolcott lived] was the open-air stage for acting-out episodes from unstable patients dumped from mental health facilities, as I discovered when I had to dodge a fully-loaded garbage can flung in my direction by a middle-aged man who still had a hospital bracelet on one of his throwing arms.

By and large he managed to side-step the garbage and keep himself more or less clean (not a drinker or much of a drug user). Wolcott is an aesthete and a literary stylist — you have to have patience for his kind of elaborate sentences to enjoy the book — and you get the sense of this style as something he developed, in part, as a protection against the threatening urban scene. (He talks about giving up on punk rock in the late 70s when it became too much about bad politics, skinheads, vomit, and spit– you can feel a visceral distaste.)

I was just checking out the customer reviews of the book on Amazon. One person comments:

For anyone even mildly curious about New York, movies, punk, journalism, writing, ballet, or the Times Square of the “Taxi Driver” era, this book should not be missed. Think of it as Woody Allen’s “Manhattan,” only with real intellectuals as opposed to fake ones.

Another less appreciative reader observes,

Just can’t imagine many general readers caring about office politics at the Village Voice, fringe critic Lester Bangs, punk rock at CBGSs, why ballet makes him woozy, the seamy 70s porn scene, Wolcott[‘s] relationship with movie critic Pauline Kael…

Ha! I guess I was a perfect reader for this, as just about all of those topics interest me to some degree. (This reader does not mention Wolcott’s discussions of Ellen Willis and Robert Christgau, a power couple in counter-cultural journalism in the early 70s; especially indelible is an account of Christgau walking around his and Willis’s tiny downtown apartment in tight red speedos.) As an occasional writer for the Voice’s music section in the 1990s, I was fascinated by the account of earlier days at the paper, and I thought Wolcott evocatively captured the special feeling of the Voice in the days before email, when all copy had to be dropped off on paper in a physical file. Human presence, embodied personalities, were so much more central to the operations of publishing, criticism and writing, all of which, Wolcott suggests, have now become much more “lonely.” When I was first doing freelance writing circa 1991, this was just beginning to change and I too remember dropping by the Spin offices to leave my copy (offering opportunities for schmoozing/ gossiping) or sitting down with Voice music editor Joe Levy to line-edit my reviews (of American Music Club and the Go-Betweens — those are the first two I remember); I recall those sessions as an intensive education in journalistic writing that I expect is difficult to come by today. (I never did meet Robert Christgau, although he was around.) Wolcott’s example shows that counter-cultural/arts journalism in the 1970s was a place where an (exceptionally) smart lower-middle-class kid without even a college degree could get an apprenticeship and eventually transform himself into a well-known writer and intellectual. This is no longer true — that arts weekly journalism institutional space no longer exists. Blogs to some degree have replaced it, but serious/rigorous arts criticism as such offers much less of a career opportunity these days (to understate it).

[btw, Wolcott comes up several times as well in Will Hermes’s new book, Love Goes to Buildings on Fire: Five Years in New York That Changed Music Forever, which I’ve so far only skimmed a bit.]

There’s a funny/poignant moment when Wolcott speculates about what might have been if he had specialized and chosen a stronger focus, as a critic, on literature, rather than covering such a wide range of topics. “I sometimes wonder what would have happened if I had found true fruition in book reviewing and taken up literary criticism as my sole vocation, putting aside childish things” (he means here primarily writing about t.v.). Next line: “I bet I’d be real bitter now.”

Slight ambiguity there: does he mean “real bitter” as opposed to just slightly bitter? The title of the book underlines Wolcott’s sense that he was very lucky in his lucked-into career, but does he feel lucky now? There’s an elegiac feeling to his story of, among other things, the decline of the Voice and of arts journalism and reviewing generally (film critic J. Hoberman was apparently just laid off from the Voice as I write this, by the way, eliminating one of the last remaining great arts critics there). I’m not sure how secure Wolcott’s present position is (he is among other things a blogger for Vanity Fair), but he obviously feels something has been lost both personally and for the intellectual scene more generally.

Of course, there are other explanations for an elegiac sense to the book, such as Wolcott’s references of the coming onslaught of AIDS in the early 1980s, at the end of his narrative. On a more personal note, his friendship with Kael also has a bittersweet feel, at least for a reader coming to his book from the Kael biography, which explains how she cut him off following his publication of the “Paulettes” piece in Vanity Fair. I was a bit surprised he does not address this falling out, perhaps because it is still too painful? or possibly simply because it occurred outside the 70s time-frame of the book, although Kael is such a major mentor figure here that it feels odd not to mention it.