I picked up Goodbye Twentieth Century: A Biography of Sonic Youth (by David Browne) at my mother in law’s house (have no idea whatsoever what it was doing there). I enjoyed it and it sent me off on an ongoing Spotify tour of Sonic Youth’s music from the past 10-15 years that I ignored or gave short shrift to at the time (e.g. I’m enjoying A Thousand Leaves).

Here are a few things I learned or found edifying:

- Reading the book and going back to some of the music, I was struck by how very Catholic Thurston Moore’s songs are. No wonder he loved Madonna! There’s the great “(I Got a) Catholic Block,” of course: “I got a Catholic block/ Inside my head/… Guess I’m out of luck.” But so many others. “She said Jesus had a twin who knew nothing about sin/ She was laughing like crazy at the trouble I’m in.” Have any Religious-Studies types gotten on this?

- I guess I always realized that the band’s name was inspired by Big Youth, but I don’t think I ever thought about their serious debt to reggae & dub. “The deep, undulating rhythms of reggae and dub had infiltrated the downtown music scene. Moore was so invested in the genre he’d begun taking subway trips to a warehouse in Queens that specialized in reggae LPs, and he told Gordon to practice at home by playing along with the bass lines on a Black Uhuru album.” This actually makes perfect sense as a way to think about the claustrophobic sound & rhythms of their early music: No Wave meets Lee Perry.

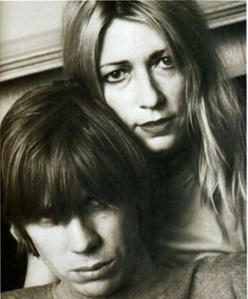

- This was a favorite moment of mine: “Phil Morrison, the up-and-coming filmmaker who’d directed the “Titanium Expose” video, starting having dreams in which [Kim] Gordon would suddenly appear, casting a judgmental eye on whatever he was doing. Talking with friends, he discovered he wasn’t alone. “Lots of people dreamed about Kim,” he says. “That was a real phenomenon. And it wasn’t about sex. She was the person you’d be most concerned about whether they think you’re cool or not.” This most perfectly encapsulated the band’s role as taste-makers, cool-hunters and -arbiters, commanding the hipster unconscious of their era. I do think some of the music absolutely stands up as some of the greatest of the era (Sister is my personal fave), but the book kind of makes the case that their greatest importance lay in their stewardship of the underground as “the imposing older siblings of the new alternative world order.” Thurston was the ultimate record-collector boy (someone hypothesizes that they invited Jim O’Roarke to join the band primarily so Thurston would have someone to go record shopping with on tour!) and Kim the arch-cool underground art/fashion diva.

- They had the kind of career that creates a bit of a letdown in the last third of the book. Their big pop push with Goo and Dirty in the mid-90s never really happened, and so there’s a little disillusionment as they soldier on making new records to diminishing expectations every year or two. That said, they’re actually really impressive as a model of a band that figured out new models for their career as they went along (e.g. Thurston’s immersion in experimental & improvised music, the band’s own SYR Records, and so on). There are some funny lines from Geffen execs or others expressing their mild frustration or resignation about the band’s increasingly willfully anti-pop moves. “The cover [of 1998’s A Thousand Leaves] was given over to “Hamster Girl,” a piece by L.A. artist Marnie Weber. In keeping with Weber’s disturbing cut-and-paste montages, “Hamster Girl” juxtaposed a small rodent with a young girl… who was sporting animal horns. ‘It was obviously not something they put together to sell a lot of records,’ recalls Farrell…”

*In the latest SY-related news, Thurston Moore has apparently just joined “black metal supergroup” Twilight. He does keep himself busy.